Bên cạnh PHÂN TÍCH ĐỀ THI THẬT TASK 2 (dạng advantages & disadvantages) Some students work while studying. Discuss the advantages and disadvantages of this trend and give your opinion?NGÀY 04/8/2020 IELTS WRITING GENERAL MÁY TÍNH (kèm bài được sửa hs đi thi), IELTS TUTOR cung cấp 🔥Creative Problem-Solving: Đề thi thật IELTS READING (IELTS Reading Recent Actual Test) - Làm bài online format computer-based, , kèm đáp án, dịch & giải thích từ vựng - cấu trúc ngữ pháp khó

I. Kiến thức liên quan

II. Làm bài online (kéo xuống cuối bài blog để xem giải thích từ vựng & cấu trúc cụ thể hơn)

III. Creative Problem-Solving: Đề thi thật IELTS READING (IELTS Reading Recent Actual Test)

READING PASSAGE 2

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 14-26, which are based on Reading Passage 2 on pages 6 and 7.

Creative Problem-Solving

Puzzle-solving is an ancient, universal practice, scholars say, and it depends on creative insight, or a primitive spark. Now, modern neuroscientists are beginning to tap its source.

A.

In a recent study, researchers at Northwestern University in the United States found that people were more likely to solve word puzzles with sudden insight when they were amused, having just seen a short comedy routine. ‘What we think is happening,’ said Dr Mark Beeman, a neuroscientist who worked on the study, ‘is that the humor, this positive mood, is lowering the brain's threshold for detecting weaker or more remote connections,’ which enable people to solve puzzles.

B.

This suggests that the appeal of puzzles goes far deeper than the pleasant rush of finding a solution. The very act of doing a puzzle typically shifts the brain into an open, playful state that is itself a pleasing escape. Unlike the social and professional mysteries in the real world, puzzles are reassuringly solvable; but like any serious problem, they require more than mere intellect to crack.

‘It’s imagination, it's inference, it's guessing; and much of it is happening subconsciously,’ said Dr Marcel Danesi, a professor of anthropology at the University of Toronto, Canada. ‘It’s all about you, using your own mind, without any method or schema, to restore order from chaos,’ Danesi said. ‘And once you have, you can sit back and say, “Hey, the rest of my life may be a disaster, but at least I have a solution”.’

C.

For almost a century scientists have used puzzles to study what they call ‘insight thinking’, the leaps of understanding that seem to come out of the blue. In one experiment, the German psychologist Karl Duncker presented people with a candle, a box of pins, and the task of attaching the candle to a wall. About a quarter of the subjects thought to use the pins to tack the box to the wall as a support—some immediately, and others after failed efforts to tack wax to the wall. According to Duncker, the creative leap seems to have been informed by subconscious cues.

In another well-known experiment, psychologists H.G. Birch and H.S. Rabinowitz challenged people to tie together two cords; the cords were hanging from the ceiling of a large room, too far apart to be grabbed at the same time. A small percentage of people solved it without any help, by tying something else to one cord and swinging it like a pendulum so that it could be caught while they held the other cord.

In some experiments, researchers gave clues to those who were stumped—for instance, by bumping into one of the strings so that it swung. Many of those who then solved the problem said they had no recollection of the clue, though it very likely registered subconsciously.

D.

All along, researchers have debated the definitions of insight and analysis, and some have concluded that the two are merely different sides of the same coin. Yet in an authoritative discussion of the research carried out so far, the psychologists Jonathan W. Schooler and Joseph Melcher concluded that the abilities most strongly correlated with insight problem-solving ‘were not significantly correlated’ with solving analytical problems. Either way, creative problem-solving usually requires both analysis and insight.

Adam Anderson, a psychologist at the University of Toronto, Canada, argues that although when people are solving problems they may move back and forth between these abilities, they are truly different brain states.

E.

At first, studies did little more than confirm that brain areas that register reward spiked in activity when people came up with a solution, that is to say, once they had completed a puzzle. However, in a series of recent studies, John Kounios, a psychologist at Drexel University in the United States, has imaged people’s brains as they prepare to tackle a puzzle, but before they’ve seen it.

Those whose brains show a particular signature of preparatory activity—one that is strongly correlated with positive moods—turn out to be more likely to solve the puzzles with sudden insight than with trial and error (the clues can be solved either way).

Previous research has also found activation of cells in a certain area of the brain when people widen or narrow their attention—say, when they filter out distractions to focus on a difficult task, like concentrating on someone’s voice in a noisy room. In the case of insight puzzle-solving, the brain seems to widen its attention, in effect making itself more susceptible to distraction.

F.

In the humor study, Beeman had college students solve word-association puzzles after watching a short video showing a stand-up comedian. Beeman found that these students solved more of the puzzles overall, and significantly more by sudden insight, compared with when they’d seen a scary or boring video beforehand.

This ‘open’ state of mind does not only apply to intellectual puzzles. In a study published last year, researchers at the University of Toronto found that people in positive moods picked up more background detail, even when they were told to block out distracting information during a computer task.

The findings fit with dozens of experiments linking positive moods to better creative problem-solving. ‘The implication is that positive mood engages this broad, ... attentional state that is both perceptual and visual,’ said Anderson. He explains that not only are people in a positive mood able to think more broadly, they are able to notice more visually.

Questions 14-19

Reading Passage 2 has six sections, A-F.

Which section contains the following information?

Write the correct letter, A-F, in boxes 14-19 on your answer sheet.

NB You may use any letter more than once.

- A claim that people enjoy the process of doing puzzles as well as finding the answers.

- A review of studies that looked at the relationship between insight and analysis.

- The finding that people were less likely to solve puzzles after viewing uninteresting or disturbing material.

- A comparison between doing puzzles and dealing with life challenges.

- A description of a study where the subjects were given hints by those conducting the research.

- Details of a study in which the focus shifted to mental activity before a puzzle is attempted.

Questions 20-23

Look at the following statements (Questions 20-23) and the list of researchers below.

Match each statement with the correct researcher, A-E.

Write the correct letter, A-E, in boxes 20-23 on your answer sheet.

- Solving a puzzle may help people facing difficulties feel better.

- Two distinctly separate functions of the brain are used when solving puzzles.

- Some subjects were able to find a solution to the puzzle they were given without knowing how they had done it.

- Seeing something funny helps people make links that may not be obvious at first.

Questions 24-26

Complete the summary below.

Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 24-26 on your answer sheet.

Kounios builds on studies of puzzle-solvers’ brain activity.

Early studies showed that when people solved a puzzle, the parts of the brain linked to reward were more active. Studies by Kounios reveal that when people are feeling 24 ................ during the preparatory stage, it is more probable that they will use insight to solve puzzles. The part of the brain that is affected is connected with the adjustment of people's attention. When someone is trying to listen to a 25 ...................... when the general sound level is high, the focus narrows. When people solve puzzles using insight, their focus becomes wider, and they are more open to 26 .........................................

IV. Dịch bài đọc Creative Problem-Solving

Giải Quyết Vấn Đề Sáng Tạo

Giải đố là một hoạt động cổ xưa và phổ quát, các học giả cho biết, và nó phụ thuộc vào sự thấu hiểu sáng tạo (creative insight) hay tia lửa nguyên thủy (primitive spark). Ngày nay, các nhà thần kinh học (neuroscientists) hiện đại đang bắt đầu khám phá nguồn gốc của nó.

A.

Trong một nghiên cứu gần đây, các nhà nghiên cứu tại Đại học Northwestern (Hoa Kỳ) phát hiện ra rằng mọi người có xu hướng giải các câu đố từ ngữ (word puzzles) bằng sự thấu hiểu đột ngột (sudden insight) khi họ được giải trí, ví dụ như sau khi xem một tiết mục hài kịch ngắn (comedy routine). Tiến sĩ Mark Beeman, nhà thần kinh học tham gia nghiên cứu, cho biết: "Chúng tôi nghĩ rằng việc hài hước, tâm trạng tích cực này đang làm giảm ngưỡng tiếp nhận (threshold) của não bộ để phát hiện các kết nối mờ nhạt hoặc xa vời hơn (remote connections)" — yếu tố giúp con người giải đố.

B.

Điều này cho thấy sức hút (appeal) của câu đố không chỉ nằm ở cảm giác hài lòng khi tìm ra đáp án. Chính hành động giải đố thường đưa não bộ vào trạng thái cởi mở (open) và vui tươi (playful), vốn là một lối thoát dễ chịu. Khác với những bí ẩn xã hội và nghề nghiệp trong đời thực, câu đố có thể giải quyết một cách đáng tin cậy (reassuringly solvable); nhưng giống như mọi vấn đề nghiêm túc, chúng đòi hỏi nhiều hơn trí tuệ thuần túy (mere intellect).

Tiến sĩ Marcel Danesi, giáo sư nhân chủng học (anthropology) tại Đại học Toronto (Canada), nói: *"Đó là trí tưởng tượng (imagination), suy luận (inference), phỏng đoán (guessing); và phần lớn diễn ra trong tiềm thức (subconsciously). Nó là việc bạn dùng chính tâm trí mình, không phương pháp hay khuôn mẫu (schema) nào, để khôi phục trật tự từ hỗn loạn (restore order from chaos). Và một khi làm được, bạn có thể thở phào: ‘Cuộc sống của tôi có thể là thảm họa, nhưng ít nhất tôi đã giải được câu đố này’".

C.

Gần một thế kỷ qua, các nhà khoa học đã dùng câu đố để nghiên cứu tư duy thấu hiểu (insight thinking) — những bước nhảy nhận thức (leaps of understanding) tưởng chừng xuất hiện từ hư không. Trong một thí nghiệm, nhà tâm lý học người Đức Karl Duncker đưa cho người tham gia một cây nến, hộp đinh và yêu cầu gắn nến lên tường. Khoảng ¼ số người nghĩ đến việc dùng đinh gắn hộp lên tường làm giá đỡ — một số nghĩ ngay, số khác sau nhiều lần thất bại khi cố gắng dán sáp vào tường. Theo Duncker, bước nhảy sáng tạo (creative leap) này dường như được thúc đẩy bởi tín hiệu tiềm thức (subconscious cues).

Trong một thí nghiệm nổi tiếng khác, các nhà tâm lý học H.G. Birch và H.S. Rabinowitz yêu cầu mọi người buộc hai sợi dây treo từ trần nhà cách xa nhau. Một số ít đã giải được bằng cách buộc vật nặng vào một dây để tạo con lắc (pendulum) và đón nó khi giữ dây còn lại. Trong vài thí nghiệm, các nhà nghiên cứu đưa gợi ý (clues) cho người bế tắc (stumped) — ví dụ, làm một sợi dây đung đưa. Nhiều người sau đó giải được nhưng không nhớ đã nhận gợi ý, dù nó có thể đã được ghi nhận tiềm thức (registered subconsciously).

D.

Các nhà nghiên cứu tranh luận về định nghĩa (definitions) của thấu hiểu (insight) và phân tích (analysis), một số kết luận rằng chúng chỉ là hai mặt của cùng một đồng xu. Tuy nhiên, trong bản phân tích uy tín (authoritative discussion) về nghiên cứu hiện có, các nhà tâm lý Jonathan W. Schooler và Joseph Melcher kết luận rằng khả năng giải đố bằng thấu hiểu "không tương quan đáng kể (not significantly correlated) với giải quyết vấn đề phân tích". Dù vậy, giải quyết vấn đề sáng tạo thường cần cả hai.

Adam Anderson, nhà tâm lý học tại Đại học Toronto (Canada), cho rằng dù mọi người có thể chuyển đổi giữa hai trạng thái khi giải đố, chúng thực sự là hai trạng thái não bộ khác biệt (different brain states).

E.

Ban đầu, nghiên cứu chỉ xác nhận rằng vùng não ghi nhận phần thưởng (brain areas that register reward) tăng đột biến hoạt động (spiked in activity) khi người ta giải được câu đố. Tuy nhiên, trong loạt nghiên cứu gần đây, John Kounios (Đại học Drexel, Hoa Kỳ) đã chụp ảnh não người chuẩn bị giải đố (preparatory activity) trước khi họ nhìn thấy câu đố.

Những người có dấu hiệu chuẩn bị (preparatory signature) liên quan đến tâm trạng tích cực (positive moods) thường giải đố bằng thấu hiểu đột ngột (sudden insight) hơn là thử và sai (trial and error). Nghiên cứu trước đó cũng phát hiện sự kích hoạt tế bào (activation of cells) ở vùng não kiểm soát sự tập trung (attention) — như khi lọc bỏ phiền nhiễu (filter out distractions) để nghe giọng ai đó trong phòng ồn. Khi giải đố bằng thấu hiểu, não bộ mở rộng tập trung (widens attention), khiến nó dễ bị phân tâm (susceptible to distraction) hơn.>> Form đăng kí giải đề thi thật IELTS 4 kĩ năng kèm bài giải bộ đề 100 đề PART 2 IELTS SPEAKING quý đang thi (update hàng tuần) từ IELTS TUTOR

F.

Trong nghiên cứu về hài hước, Beeman yêu cầu sinh viên giải câu đố liên tưởng từ (word-association puzzles) sau khi xem video hài. Kết quả cho thấy họ giải được nhiều câu đố hơn, đặc biệt bằng thấu hiểu, so với khi xem video đáng sợ hoặc nhàm chán.

Trạng thái cởi mở (open) này không chỉ áp dụng cho câu đố trí tuệ. Trong nghiên cứu năm ngoái, các nhà nghiên cứu tại Đại học Toronto phát hiện người có tâm trạng tích cực tiếp nhận chi tiết nền (background detail) tốt hơn, kể cả khi được yêu cầu loại bỏ thông tin gây nhiễu (block out distracting information).

Phát hiện này phù hợp với hàng chục thí nghiệm cho thấy tâm trạng tích cực (positive moods) giúp giải quyết vấn đề sáng tạo tốt hơn. Anderson giải thích: "Tâm trạng tích cực kích hoạt trạng thái tập trung bao quát (broad) cả nhận thức (perceptual) lẫn thị giác (visual)".

Câu hỏi 14-19

Bài đọc có 6 phần, A-F.

Phần nào chứa thông tin sau?

Viết đáp án đúng (A-F) vào ô 14-19.

Lưu ý: Mỗi chữ cái có thể được dùng nhiều lần.

Một tuyên bố rằng mọi người thích quá trình giải đố lẫn việc tìm đáp án.

Tổng quan các nghiên cứu về mối quan hệ giữa thấu hiểu và phân tích.

Phát hiện rằng mọi người ít giải được đố hơn sau khi xem nội dung nhàm chán hoặc tiêu cực.

So sánh giữa giải đố và xử lý thách thức cuộc sống.

Mô tả nghiên cứu nơi người tham gia được nhận gợi ý từ nhóm nghiên cứu.

Chi tiết về nghiên cứu tập trung vào hoạt động não trước khi giải đố.

Câu hỏi 20-23

Nối các phát biểu (20-23) với nhà nghiên cứu tương ứng (A-E).

Giải đố có thể giúp người gặp khó khăn cảm thấy tốt hơn.

Hai chức năng não riêng biệt được dùng khi giải đố.

Một số người giải được đố mà không biết làm cách nào.

Xem thứ gì đó hài hước giúp mọi người tạo kết nối không rõ ràng.

Danh sách nhà nghiên cứu:

A. Mark Beeman

B. Marcel Danesi

C. Karl Duncker

D. Jonathan W. Schooler và Joseph Melcher

E. Adam Anderson

Câu hỏi 24-26

Hoàn thành tóm tắt sau.

Chọn MỘT TỪ DUY NHẤT từ bài đọc.

Kounios mở rộng nghiên cứu về hoạt động não (brain activity) khi giải đố. Nghiên cứu ban đầu cho thấy khi giải đố, vùng não liên quan phần thưởng (reward) hoạt động mạnh. Nghiên cứu của Kounios tiết lộ rằng nếu mọi người cảm thấy 24. ________ trong giai đoạn chuẩn bị, họ có xu hướng dùng thấu hiểu (insight) để giải. Vùng não bị ảnh hưởng liên quan đến điều chỉnh sự tập trung (attention). Khi ai đó cố nghe 25. ________ trong môi trường ồn, sự tập trung thu hẹp. Khi giải đố bằng thấu hiểu, sự tập trung mở rộng, họ dễ tiếp nhận 26. ________.

V. Giải thích từ vựng Creative Problem-Solving

VI. Giải thích cấu trúc ngữ pháp khó Creative Problem-Solving

VII. Đáp án Creative Problem-Solving

14. B — 15. D 16. F 17. B 18. C 19. E 20. B 21. D 22. C 23. A 24. positive 25. voice 26. distraction

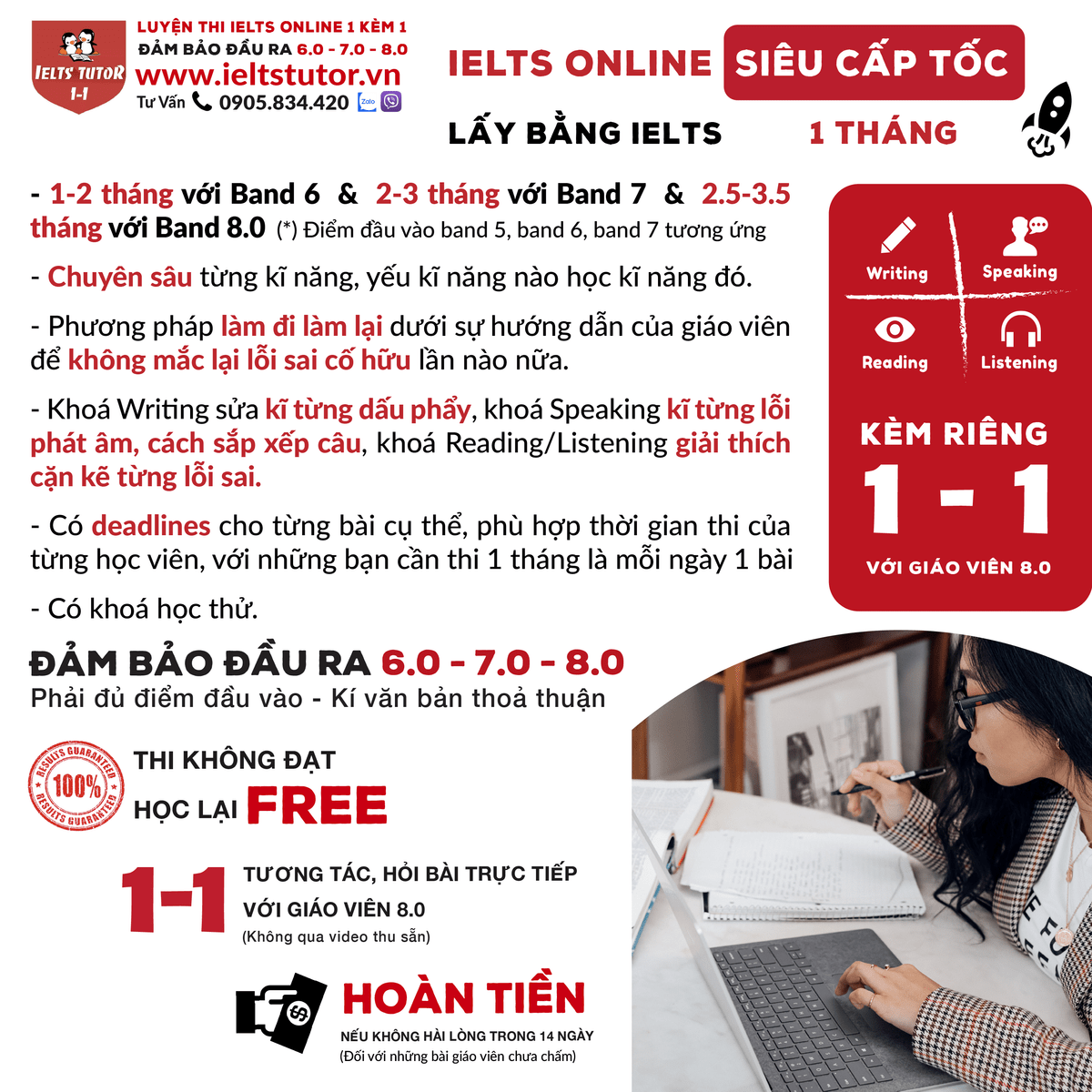

Các khóa học IELTS online 1 kèm 1 - 100% cam kết đạt target 6.0 - 7.0 - 8.0 - Đảm bảo đầu ra - Thi không đạt, học lại FREE

>> Thành tích học sinh IELTS TUTOR với hàng ngàn feedback được cập nhật hàng ngày