IELTS TUTOR cung cấp 🔥Travel Accounts: Đề thi thật IELTS READING (IELTS Reading Recent Actual Test) - Làm bài online format computer-based, , kèm đáp án, dịch & giải thích từ vựng - cấu trúc ngữ pháp khó & GIẢI ĐÁP ÁN VỚI LOCATION

I. Kiến thức liên quan

II. Làm bài online (kéo xuống cuối bài blog để xem giải thích từ vựng & cấu trúc cụ thể hơn)

III. Travel Accounts: Đề thi thật IELTS READING (IELTS Reading Recent Actual Test)

Travel Accounts

A

There are many reasons why individuals have traveled beyond their own societies. Some travelers may have simply desired to satisfy curiosity about the larger world. Until recent times, however, trade, business dealings, diplomacy, political administration, military campaigns, exile, flight from persecution, migration, pilgrimage, missionary efforts, and the quest for economic or educational opportunities were more common inducements for foreign travel than was a mere curiosity. While the travelers’ accounts give much valuable information on these foreign lands and provide a window for the understanding of the local cultures and histories, they are also a mirror to the travelers themselves, for these accounts help them to have a better understanding of themselves.

B

Records of foreign travel appeared soon after the invention of writing, and fragmentary travel accounts appeared in both Mesopotamia and Egypt in ancient times. After the formation of large, imperial states in the classical world, travel accounts emerged as a prominent literary genre in many lands, and they held especially strong appeal for rulers desiring useful knowledge about their realms. The Greek historian Herodotus reported on his travels in Egypt and Anatolia in researching the history of the Persian wars. The Chinese envoy Zhang Qian described much of central Asia as far west as Bactria (modern-day Afghanistan) on the basis of travels undertaken in the first century BC while searching for allies for the Han dynasty. Hellenistic and Roman geographers such as Ptolemy, Strabo, and Pliny the Elder relied on their own travels through much of the Mediterranean world as well as reports of other travelers to compile vast compendia of geographical knowledge.

C

During the postclassical era (about 500 to 1500 CE), trade and pilgrimage emerged as major incentives for travel to foreign lands. Muslim merchants sought trading opportunities throughout much of the eastern hemisphere. They described lands, peoples, and commercial products of the Indian Ocean basin from East Africa to Indonesia, and they supplied the first written accounts of societies in sub-Saharan west Africa. While merchants set out in search of trade and profit, devout Muslims traveled as pilgrims to Mecca to make their hajj and visit the holy sites of Islam. Since the prophet Muhammad’s original pilgrimage to Mecca, untold millions of Muslims have followed his example, and thousands of hajj accounts have related their experiences. One of the best known Muslim travelers, Ibn Battuta, began his travels with the hajj but then went on to visit central Asia, India, China, sub-Saharan Africa, and parts of Mediterranean Europe before returning finally to his home in Morocco. East Asian travelers were not quite so prominent as Muslims during the postclassical era, but they too followed many of the highways and sea lanes of the eastern hemisphere. Chinese merchants frequently visited Southeast Asia and India, occasionally venturing even to east Africa, and devout East Asian Buddhists undertook distant pilgrimages. Between the 5th and 9th centuries CE, hundreds and possibly even thousands of Chinese Buddhists traveled to India to study with Buddhist teachers, collect sacred texts, and visit holy sites. Written accounts recorded the experiences of many pilgrims, such as Faxian, Xuanzang, and Yijing. Though not so numerous as the Chinese pilgrims, Buddhists from Japan, Korea, and other lands also ventured abroad in the interests of spiritual enlightenment.

D

Medieval Europeans did not hit the roads in such large numbers as their Muslim and east Asian counterparts during the early part of the postclassical era, although gradually increasing crowds of Christian pilgrims flowed to Jerusalem, Rome, Santiago de Compostela (in northern Spain), and other sites. After the 12th century, however, merchants, pilgrims, and missionaries from medieval Europe traveled widely and left numerous travel accounts, of which Marco Polo’s description of his travels and sojourn in China is the best known. As they became familiar with the larger world of the eastern hemisphere – and the profitable commercial opportunities that it offered – European peoples worked to find new and more direct routes to Asian and African markets. Their efforts took them not only to all parts of the eastern hemisphere but eventually to the Americas and Oceania as well.

E

If Muslim and Chinese peoples dominated travel writing in postclassical times, European explorers, conquerors, merchants, and missionaries took center stage during the early modern era (about 1500 to 1800 CE). By no means did Muslim and Chinese travel come to a halt in early modern times. But European peoples ventured to the distant corners of the globe, and European printing presses churned out thousands of travel accounts that described foreign lands and peoples for a reading public with an apparently insatiable appetite for news about the larger world. The volume of travel literature was so great that several editors, including Giambattista Ramusio, Richard Hakluyt, Theodore de Bry, and Samuel Purchas, assembled numerous travel accounts and made them available in enormous published collections.

F

During the 19th century, European travelers made their way to the interior regions of Africa and the Americas, generating a fresh round of travel writing as they did so. Meanwhile, European colonial administrators devoted numerous writing to the societies of their colonial subjects, particularly in Asian and African colonies they established. By midcentury, attention was flowing also in the other direction. Painfully aware of the military and technological prowess of European and Euro-American societies, Asian travelers, in particular, visited Europe and the United States in hopes of discovering principles useful for the reorganization of their own societies. Among the most prominent of these travelers who made extensive use of their overseas observations and experiences in their own writing were the Japanese reformer Fukuzawa Yukichi and the Chinese revolutionary Sun Yat-sen.

G

With the development of inexpensive and reliable means of mass transport, the 20th century witnessed explosions both in the frequency of long-distance travel and in the volume of travel writing. While a great deal of travel took place for reasons of business, administration, diplomacy, pilgrimage, and missionary work, as in ages past, increasingly effective modes of mass transport made it possible for new kinds of travel to flourish. The most distinctive of them was mass tourism, which emerged as a major form of consumption for individuals living in the world’s wealthy societies. Tourism enabled consumers to get away from home to see the sights in Rome, take a cruise through the Caribbean, walk the Great Wall of China, visit some wineries in Bordeaux, or go on safari in Kenya. A peculiar variant of the travel account arose to meet the needs of these tourists: the guidebook, which offered advice on food, lodging, shopping, local customs, and all the sights that visitors should not miss seeing. Tourism has had a massive economic impact throughout the world, but other new forms of travel have also had considerable influence in contemporary times. Recent times have seen unprecedented waves of migration, for example, and numerous migrants have sought to record their experiences and articulate their feelings about life in foreign lands. Recent times have also seen an unprecedented development of ethnic consciousness, and many are the intellectuals and writers in the diaspora who have visited the homes of their ancestors to see how much of their forebears’ values and cultural traditions they themselves have inherited. Particularly notable among their accounts are the memoirs of Malcolm X and Maya Angelou describing their visits to Africa.

Questions 9-13

Choose the correct letter, A, B, C or D.

Write your answers in boxes 9-13 on your answer sheet.

Why did some people travel in the early days?

A to do research on themselves

B to write travel books

C to have a better understanding of other people and places

D to study local cultureThe travelers’ accounts are a mirror to themselves,

A because they help them to be aware of local histories.

B because travelers are curious about the world.

C because travelers could do more research on the unknown.

D because they reflect the writers’ own experience and social life.Most of the people who went to holy sites during the early part of the postclassical era are

A Europeans.

B Muslim and East Asians.

C Americans.

D Greeks.During the early modern era, a large number of travel books were published to

A provide what the public wants.

B encourage the public’s feedback.

C gain profit.

D prompt trips to the new world.What stimulated the market for traveling in the 20th century?

A the wealthy

B travel books

C delicious food

D mass transport

IV. Dịch bài đọc Travel Accounts

Những Ghi Chép Về Du Hành

A

Có nhiều lý do khiến mọi người du hành vượt ra khỏi xã hội của họ. Một số du khách có thể chỉ đơn giản muốn thỏa mãn sự tò mò (curiosity, inquisitiveness, wonder, interest) về thế giới rộng lớn hơn. Tuy nhiên, cho đến thời gian gần đây, thương mại (trade, commerce, business, exchange), giao dịch kinh doanh (business dealings, transactions, negotiations, agreements), ngoại giao (diplomacy, international relations, foreign affairs, statecraft), quản trị chính trị (political administration, governance, ruling, leadership), chiến dịch quân sự (military campaigns, operations, offensives, expeditions), lưu đày (exile, banishment, expulsion, deportation), chạy trốn sự đàn áp (flight from persecution, escape from oppression, fleeing repression, seeking refuge), di cư (migration, relocation, movement, resettlement), hành hương (pilgrimage, religious journey, sacred voyage, spiritual quest), truyền giáo (missionary efforts, evangelism, proselytizing, religious outreach), và tìm kiếm cơ hội kinh tế hoặc giáo dục (quest for economic or educational opportunities, pursuit of financial or academic prospects, search for better livelihood or learning, ambition for prosperity or knowledge) phổ biến hơn nhiều so với sự tò mò đơn thuần (mere curiosity, simple wonder, basic inquisitiveness, plain interest). Trong khi những ghi chép về du hành (travel accounts, travelogues, journey records, expedition reports) cung cấp nhiều thông tin giá trị về các vùng đất xa lạ và mở ra một cánh cửa (window, portal, gateway, passage) giúp hiểu rõ hơn về nền văn hóa và lịch sử địa phương, chúng cũng là một tấm gương phản chiếu (mirror, reflection, looking glass, self-portrait) chính các du khách, vì những ghi chép này giúp họ có cái nhìn sâu sắc hơn về bản thân mình.

B

Những ghi chép về du hành xuất hiện ngay sau khi chữ viết (writing, script, inscription, notation) ra đời, và các ghi chép rời rạc (fragmentary travel accounts, incomplete travel records, partial expedition notes, scattered travel narratives) đã được tìm thấy ở cả Lưỡng Hà (Mesopotamia, ancient Iraq, Babylonian civilization, Assyrian empire) và Ai Cập (Egypt, land of pharaohs, Nile civilization, ancient Kemet) thời cổ đại. Sau khi các quốc gia đế chế lớn (large imperial states, vast empires, powerful dynasties, expansive kingdoms) được hình thành trong thế giới cổ điển, các ghi chép về du hành xuất hiện như một thể loại văn học nổi bật (prominent literary genre, well-known writing style, distinguished literary form, eminent narrative category) ở nhiều vùng đất, và chúng đặc biệt hấp dẫn đối với các nhà cầm quyền (rulers, monarchs, sovereigns, leaders) muốn có kiến thức hữu ích về lãnh thổ của mình. Nhà sử học (historian, chronicler, annalist, scholar) Hy Lạp Herodotus đã báo cáo về những chuyến đi của mình đến Ai Cập và Anatolia khi nghiên cứu lịch sử các cuộc chiến tranh Ba Tư. Sứ giả Trung Quốc Zhang Qian đã mô tả nhiều khu vực thuộc Trung Á (central Asia, heart of Asia, inner Asia, mid-Asia), xa đến tận Bactria (modern-day Afghanistan, ancient Balkh, Bactrian kingdom, historical region of Bactra), dựa trên các chuyến đi thực hiện vào thế kỷ thứ nhất trước Công nguyên để tìm kiếm đồng minh cho triều đại nhà Hán (Han dynasty, imperial Han, ruling house of Han, Chinese Han empire). Các nhà địa lý (geographers, cartographers, topographers, mapmakers) Hy Lạp và La Mã như Ptolemy, Strabo và Pliny the Elder đã dựa vào các cuộc du hành của chính họ qua phần lớn thế giới Địa Trung Hải (Mediterranean world, Mare Nostrum, Mediterranean basin, coastal Europe and North Africa) cũng như các báo cáo từ những du khách khác để biên soạn các tuyển tập khổng lồ (vast compendia, extensive collections, massive anthologies, comprehensive archives) về kiến thức địa lý.

C

Trong thời kỳ hậu cổ điển (khoảng 500 đến 1500 CN), thương mại (trade, commerce, exchange, business) và hành hương (pilgrimage, spiritual journey, religious voyage, sacred travel) nổi lên như những động lực chính để du hành đến các vùng đất xa lạ. Các thương nhân Hồi giáo đã tìm kiếm cơ hội buôn bán trên khắp bán cầu Đông (eastern hemisphere, Orient, eastern world, Asiatic region). Họ mô tả các vùng đất, con người và sản phẩm thương mại của lưu vực Ấn Độ Dương (Indian Ocean basin, Indo-Pacific region, maritime trade routes, southern oceanic sphere), từ Đông Phi đến Indonesia, và họ cũng là những người đầu tiên cung cấp các ghi chép bằng văn bản về các xã hội ở Tây Phi cận Sahara. Trong khi các thương nhân lên đường để tìm kiếm lợi nhuận thương mại (trade and profit, commercial gains, business earnings, economic benefits), những người Hồi giáo mộ đạo đã đi hành hương đến Mecca để thực hiện hajj (hajj, pilgrimage to Mecca, sacred Islamic journey, spiritual voyage) và thăm các địa điểm linh thiêng của đạo Hồi.

D

Người châu Âu thời trung cổ không đi du lịch nhiều như những đối tác (counterparts, equivalents, peers, equals) Hồi giáo và Đông Á của họ trong giai đoạn đầu của thời kỳ hậu cổ điển, mặc dù dần dần ngày càng nhiều đám đông (crowds, throngs, gatherings, masses) khách hành hương Cơ đốc đổ về Jerusalem, Rome, Santiago de Compostela (ở phía bắc Tây Ban Nha) và các địa điểm khác. Tuy nhiên, sau thế kỷ 12, các thương nhân (merchants, traders, dealers, vendors), khách hành hương và nhà truyền giáo (missionaries, evangelists, preachers, proselytizers) từ châu Âu trung cổ đã đi du lịch rộng rãi và để lại nhiều tường thuật (accounts, narratives, chronicles, reports) về chuyến đi, trong đó mô tả của Marco Polo về chuyến du hành và lưu trú (sojourn, stay, residence, stopover) của ông ở Trung Quốc là nổi tiếng nhất. Khi họ trở nên quen thuộc với thế giới rộng lớn hơn của bán cầu Đông - và những cơ hội thương mại (commercial opportunities, business prospects, trade possibilities, market openings) sinh lợi mà nó mang lại - người châu Âu đã cố gắng tìm các tuyến đường (routes, paths, passages, tracks) mới và trực tiếp hơn đến các thị trường châu Á và châu Phi. Những nỗ lực của họ không chỉ đưa họ đến mọi nơi trên bán cầu Đông mà cuối cùng còn đến cả châu Mỹ và châu Đại Dương.

E

Nếu người Hồi giáo và người Trung Quốc chiếm ưu thế trong việc viết về du hành vào thời hậu cổ điển, thì các nhà thám hiểm (explorers, adventurers, voyagers, pioneers), kẻ chinh phục (conquerors, invaders, subjugators, vanquishers), thương nhân và nhà truyền giáo châu Âu đã trở thành trung tâm trong thời kỳ cận đại (khoảng 1500 đến 1800 CN). Không có nghĩa là du hành của người Hồi giáo và người Trung Quốc đã dừng lại (come to a halt, cease, stop, terminate) vào thời kỳ này. Nhưng người châu Âu đã mạo hiểm (ventured, dared, embarked, journeyed) đến những góc xa xôi (distant corners, remote areas, far reaches, extreme edges) của thế giới, và các nhà in (printing presses, publishing houses, print shops, printing firms) châu Âu đã sản xuất hàng loạt (churned out, mass-produced, generated, reproduced) hàng nghìn bản tường thuật du hành mô tả các vùng đất và dân tộc xa lạ cho một công chúng mê đọc sách (reading public, literate audience, book enthusiasts, bibliophiles) với một sự thèm khát không thể nguôi (insatiable appetite, unquenchable thirst, unrelenting desire, voracious hunger) đối với tin tức về thế giới rộng lớn hơn. Khối lượng văn học du hành (travel literature, travel writing, expedition records, journey narratives) lớn đến mức một số biên tập viên (editors, compilers, curators, redactors), bao gồm Giambattista Ramusio, Richard Hakluyt, Theodore de Bry và Samuel Purchas, đã tập hợp (assembled, compiled, collected, gathered) nhiều bản tường thuật du hành và xuất bản chúng thành những bộ sách khổng lồ.>> Form đăng kí giải đề thi thật IELTS 4 kĩ năng kèm bài giải bộ đề 100 đề PART 2 IELTS SPEAKING quý đang thi (update hàng tuần) từ IELTS TUTOR

F

Trong thế kỷ 19, những lữ khách (travelers, voyagers, wayfarers, globetrotters) châu Âu đã tìm đường đến (made their way to, reached, arrived at, ventured into) các vùng sâu trong châu Phi và châu Mỹ, tạo ra một làn sóng mới của văn học du hành khi họ làm vậy. Trong khi đó, các quan chức thuộc địa (colonial administrators, imperial officials, colonial governors, colonial officers) châu Âu đã viết nhiều về các xã hội (societies, communities, civilizations, cultures) của những thần dân (subjects, subordinates, vassals, dependents) thuộc địa của họ, đặc biệt là trong các thuộc địa ở châu Á và châu Phi mà họ thiết lập. Đến giữa thế kỷ, sự chú ý cũng bắt đầu chảy theo hướng ngược lại (flowing in the other direction, reversing course, shifting backward, turning around). Nhận thức sâu sắc về sức mạnh quân sự và công nghệ (military and technological prowess, armed superiority, defense capabilities, technological dominance) của các xã hội châu Âu và châu Âu-Mỹ, đặc biệt là các lữ khách châu Á (Asian travelers, Eastern voyagers, Far Eastern explorers, oriental wanderers) đã đến thăm châu Âu và Hoa Kỳ với hy vọng khám phá ra những nguyên tắc (principles, doctrines, tenets, precepts) hữu ích để tái tổ chức (reorganization, restructuring, reform, revamping) xã hội của chính họ. Trong số những nhà cải cách (reformers, innovators, revolutionaries, progressives) tiêu biểu nhất, những người đã tận dụng rộng rãi các quan sát (observations, insights, findings, examinations) và trải nghiệm (experiences, encounters, adventures, exposures) ở nước ngoài trong bài viết của họ, có nhà cải cách Nhật Bản Fukuzawa Yukichi và nhà cách mạng Trung Quốc Tôn Trung Sơn.

G

Với sự phát triển của các phương tiện vận chuyển (means of transport, transportation methods, transit systems, conveyance modes) đại chúng giá rẻ và đáng tin cậy, thế kỷ 20 đã chứng kiến sự bùng nổ (explosions, surges, outbursts, upsurges) cả về tần suất (frequency, regularity, recurrence, rate) của du hành đường dài và khối lượng (volume, quantity, magnitude, amount) của văn học du hành. Trong khi một lượng lớn các chuyến du hành diễn ra vì lý do kinh doanh (business, commerce, trade, entrepreneurship), quản lý hành chính (administration, governance, bureaucracy, management), ngoại giao (diplomacy, international relations, statecraft, negotiations), hành hương và truyền giáo, như trong các thời đại trước, thì các phương thức vận chuyển (modes of transport, transport systems, transit methods, vehicular means) ngày càng hiệu quả đã giúp những loại hình du hành mới phát triển mạnh mẽ. Đáng chú ý nhất trong số đó là du lịch đại chúng (mass tourism, large-scale travel, mainstream tourism, commercial tourism), thứ đã xuất hiện (emerged, arisen, surfaced, developed) như một hình thức tiêu dùng (consumption, expenditure, utilization, usage) chính của các cá nhân sống trong các xã hội giàu có (wealthy societies, affluent nations, prosperous communities, well-off regions). Du lịch cho phép du khách (tourists, travelers, sightseers, vacationers) rời khỏi nhà để ngắm nhìn các danh lam thắng cảnh (sights, landmarks, attractions, marvels) ở Rome, đi du thuyền (cruise, voyage, sailing, expedition) qua vùng Caribbean, đi bộ trên Vạn Lý Trường Thành, thăm một số nhà máy rượu (wineries, vineyards, distilleries, wine estates) ở Bordeaux, hoặc tham gia một chuyến safari (safari, wildlife tour, jungle expedition, game drive) ở Kenya. Một biến thể đặc biệt của bản tường thuật du hành đã xuất hiện (arose, came into existence, materialized, unfolded) để đáp ứng nhu cầu của những du khách này: sách hướng dẫn du lịch (guidebook, travel manual, tourist handbook, vacation guide), cung cấp lời khuyên về ẩm thực (food, cuisine, gastronomy, culinary arts), chỗ ở (lodging, accommodation, residence, dwellings), mua sắm (shopping, retail therapy, commercial transactions, consumerism), phong tục địa phương (local customs, traditions, practices, cultural norms) và tất cả những danh thắng mà du khách không nên bỏ lỡ.

V. Giải thích từ vựng Travel Accounts

VI. Giải thích cấu trúc ngữ pháp khó Travel Accounts

VII. Đáp án Travel Accounts

Persian wars

allies

geographical knowledge

pilgrimage

Buddhist teachers

colonies they conquer

principles for the reorganization of their societies

wealthy

C

D

B

A

D

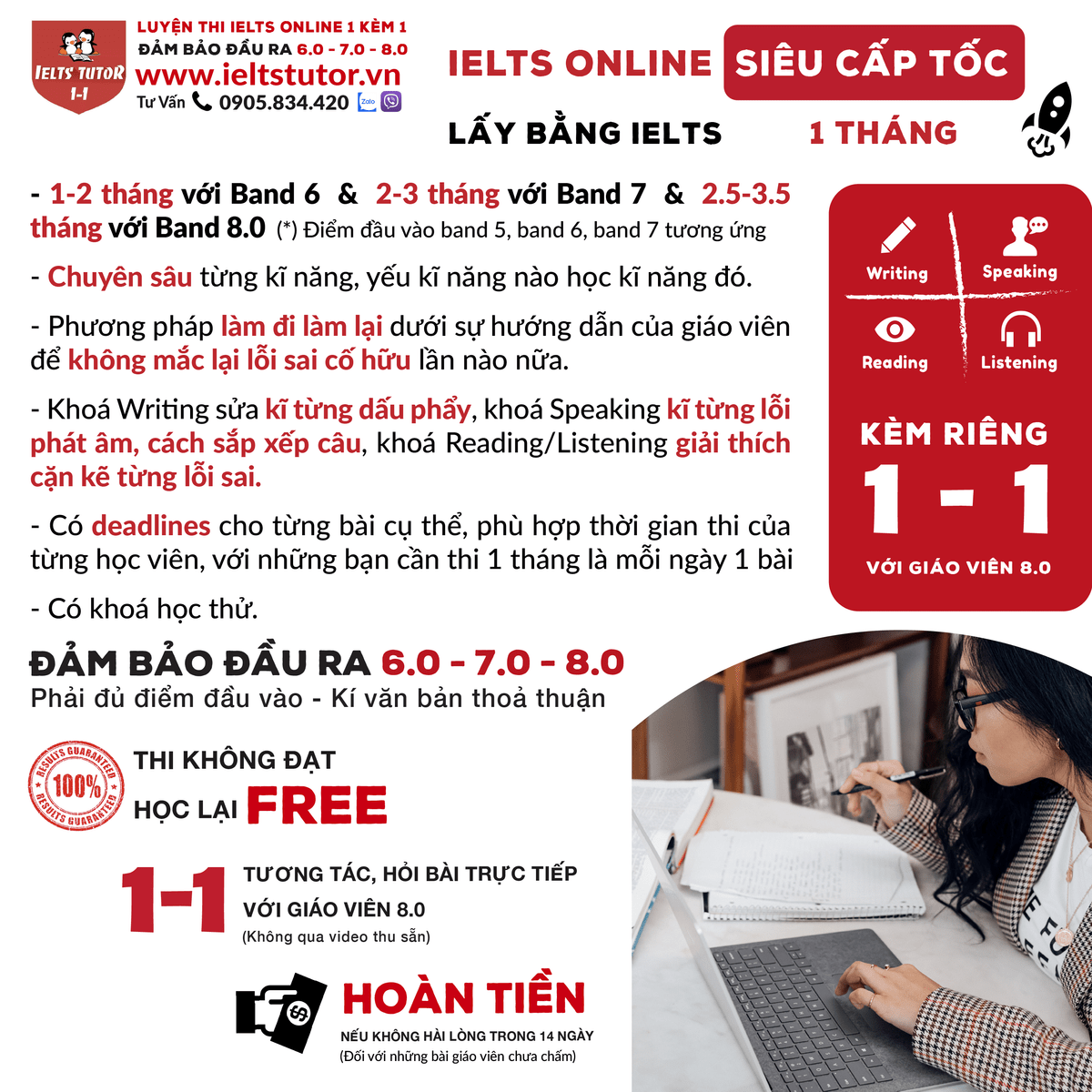

Các khóa học IELTS online 1 kèm 1 - 100% cam kết đạt target 6.0 - 7.0 - 8.0 - Đảm bảo đầu ra - Thi không đạt, học lại FREE

>> Thành tích học sinh IELTS TUTOR với hàng ngàn feedback được cập nhật hàng ngày